OFFERINGS TO THE GOD OF SPEED

The Man who Built the World's Fastest Indian

Words: Stuart Barker

Pictures courtesy of the Munro family

Everybody who's ever owned a

bike has wanted to know how fast it goes. It’s human nature. The only problem

is that, once you’ve ridden your bike flat out, you just know you’re

going to want to go even faster. That’s human nature too. But while most of us

are content to buy a few aftermarket parts to slightly increase the bhp of our

bikes, some people feel the need to take things further. And in Burt Munro’s

case, much, much further.

In 1920, Munro bought an Indian Scout capable of doing

50mph. After spending the next 46 years modifying it in his shed, the

63-year-old grandfather took the vintage machine to the Bonneville Salt flats

in Utah, USA and clocked an unofficial speed of 212mph - more than four times

the bike’s original top speed. The equivalent today would be taking a stock

Suzuki GSX-R1000 or Yamaha R1 and modifying it - designing and building all the

parts yourself, on a shoestring budget, and without using 'cheats' like turbos

or nitrous. - until it was capable of speeds exceeding 680mph!

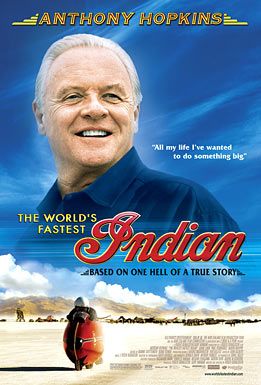

Most people now know of Burt Munro through the 2005 movie The

World’s Fastest Indian. For many cinema-goers, Sir Anthony Hopkins’

portrayal of the New Zealander was so convincing that, in their minds at least,

he is Burt Munro. But what was the real Munro like? And why did he

devote his life to the pursuit of speed? What possessed him to live and sleep in

his shed for a quarter of a century only taking half a day off for Christmas so

he could achieve that one perfect run through the Bonneville timing lights? TWO

tracked down Munro’s son, John, in New Zealand, to find out what his father was

really like and why he dedicated his life to making offerings to the God of

Speed. The pictures published here are from the Munro family’s private

collection and most have never been seen before.

Herbert J. 'Burt' Munro was born near Invercargill at the

southern extremities of New Zealand's South Island. ‘It was originally spelt

Bert’ says Munro’s son, ‘but the Americans decided to call him Burt so he went

along with it.’

At 15 years old, Munro bought his first bike - a Douglas - and his life long love affair with motorcycles began. In 1917 at the age of 18, he paid £50 for a new Clyno with sidecar. After removing the chair, Munro raced the bike in local meets and started setting a few local speed records at the Fortrose circuit near Invercargill. But it wasn't until 1920 that Burt Munro encountered the machine which would change his life. It was a 1919 Indian Scout - a 600cc, V-twin with side valves, a three-speed, hand-change gearbox and a foot-operated clutch. The engine was housed in a double down-tube cradle frame which had no rear suspension but there was about two inches of travel at the front thanks to a leaf spring. Munro fell in love with the machine and bought it from the small dealers in Invercargill. To this day, the bike has been referred to as a 1920 model (Burt even had this painted on the bodywork) but John Munro can now correct this universal misconception. ‘The Indian was actually a 1919 model’ he admits ‘but Burt bought it in 1920 so he always called it a 1920 model.’

|

| The Indian in 1940 |

The first major modifications to the bike were made in 1926. This consisted mainly of removing surplus items to reduce weight and some alterations to the riding position. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Munro designed and built his own four-cam system to replace the standard two-cam, push-rod set-up and converted the bike to run with overhead valves. Over the years, Munro would make his own barrels, pistons, flywheels, cams and followers, and even his own lubrication system. Impressive as all this was, it was Munro's unorthodox methods and the fact that he was forced to operate on a shoestring budget which made his engineering feats so remarkable. For instance, he made barrels from pieces of cast iron gas pipe which he scrounged from the local gas company after they’d been dug up for replacement. Munro believed that after spending so long underground, the iron would be 'well seasoned' and therefore ideal for the job. He hand-carved con-rods from an old tractor axle, carved the tread off normal tyres with a kitchen knife to make high speed slick tyres, and one report even had him casting pistons in holes dug on the local beach! This, like so many stories surrounding Munro is a myth as his son reveals. ‘Someone must have heard about the technique of sand-casting and came up with that one. It’s not true. There are so many myths about my dad. When we were filming at Bonneville people kept coming up to me and asking if all these weird stories were true. It happens here in New Zealand too.’

|

| Riding a Velocette in the New Zealand Grand Prix at Cust in 1938 |

For Burt Munro, time spent on even the most laborious jobs

was always time well spent. 'It is almost impossible for me to give you a true

picture of the time I have spent on my cycles' Munro wrote to a fellow

enthusiast in 1970. ' The last 22 years has been full time and for one stretch

of 10 years I put in 16 hours every day, but on Christmas Day only took the

afternoon off.'

Wayne Alexander of Britten Motorcycles - who built two

replicas of the Munro Special for the movie - is amazed at the time and effort

Munro put into his project. He says 'Burt would spend 40 hours hand-filing a

piece that could have been done on a mill in 30 minutes.' Alexander also

marvels at Munro’s skill in designing and building complex working parts

without technical drawings to guide him. ‘He was remarkable in that he didn’t

do a lot of drawings’ he says. ‘He could hold huge images in his head.’

According to Munro’s son, his engineering talents were innate. ‘His engineering skills were all self-taught. There’s a bit of a mechanical bent in the family. One of his uncles invented some agricultural machinery which was sold around the world and I’ve inherited it to some degree - I've invented things and patented them.’

|

| Burt reached a speed of 123.83mph on the beach in 1953 |

Munro became so obsessed with his quest for speed that he

eventually split from his family and worked full time on his bike. His son

recalls ‘My mum and dad separated in late 1945. About five years after that dad

sold the family house and I went to live with my mum and sisters. After selling

the house dad bought a plot on the other side of town and built a concrete shed

where he worked on his bikes, slept and lived.’

John Munro remembers helping his father out in the shed at

the family home and even riding pillion on what would become the world‘s

fastest Indian. ‘I used to help my dad work on his bikes, particularly just

prior to, and during, the war years. Occasionally, if I was lucky and dad was

home at the time I’d get taken to school on the Indian or whatever bike was

around at the time.’

Although reluctant to speak on behalf of his mother - Burt’s widow - John Munro concedes that she may never have forgiven Burt for spending so much time - and precious money - on his bikes. ‘I can’t really answer for my mother but obviously when you’re living through a depression and money is being spent on other things, then I’m quite sure there was some resentment about the time and money Burt was spending on bikes.’

|

| Burt and his beloved Indian in 1962 |

At time of writing, Munro’s wife had not seen the movie made about her

estranged husband as John explains. ‘My mum hasn’t seen the film yet and we

haven’t asked her if she wants to see it. She’ll say in her own time if she

wants to see it. She has ups and downs about the whole thing but I think she’s

quietly pleased about it.’

John himself is delighted with the film. ‘Myself and my

sisters were absolutely thrilled when we saw the movie for the first time. I

don’t think my dad would have believed they’d make a movie about him. I met

Roger Donaldson in 1971 when he made a documentary about my dad called ‘Offerings

to the God of Speed.’ Roger said then that he hadn’t done my dad justice

and that he wanted to make a feature movie about him. I told him he was nuts.

Dad just sort of shrugged in his usual way and said ‘suit yourself fella.’

Once he began attempting speed records, Munro soon realised

he needed a bigger engine so, in incremental stages, he gradually bored the

bike out to 850cc, 920cc, 953cc and, ultimately, 1000cc. It may sound pretty

straightforward, but simply keeping an engine running with almost double its

original displacement is a feat in itself - imagine the stresses that would be

put on a Fireblade bored out to 2000cc!

So why didn’t he simply buy a more modern bike with a larger capacity and save himself a whole load of trouble? ‘He just liked the personal challenge of making an old bike go faster’ says John Munro. ‘He liked to confound the experts - if someone told him it couldn’t be done, he liked to prove otherwise. It was just the challenge of seeing what he could do with it. I don’t know exactly what he paid for the Indian but it was somewhere in the order of $130-$150.'

|

| The second shell Burt used at Bonneville in 1967 |

On top of boring the bike out to twice its size, Munro also successfully converted the Scout from a flat-head to a push-rod, OHV configuration. Inevitably, there was a price to pay for asking so much from an ancient machine. As the movie depicts, Munro had the legend ‘Offerings to the God of Speed’ painted on the inside of his shed. Below it were stacked hundreds of failed and broken parts, usually due to con-rods and cylinder sleeves not being able to hack the pace Munro demanded of them. Over a 50 year period, Burt estimated he had suffered 250 engine blow-ups.

|

| At work on the cams, 1965 |

But however many setbacks he had, Munro never gave up and

his motto remained the same: ‘If it’s broken, fix it and try again.’ After

breaking 50 standard connecting rods, he spent five months making his own out

of an old Ford truck axle. The man simply didn’t know how to quit.

Munro had a long history in motorcycle sport before

attempting world speed records at Bonneville. In the 1920s he rode Speedway in

Australia before returning to New Zealand with his young family when the Great

Depression struck. But while he raced in many local events, his real obsession

was with outright top speed. In 1948, Munro packed in his day job (he rode all

over New Zealand on bikes trying to sell them to farmers) and dedicated the

rest of his life to speed. His early achievements included setting the New

Zealand record in 1940 with a speed of 120.8mph - a record which stood until

1952. He set a further six records in his home country - including a flying

half mile at 143.6mph in 1957 - before taking up the challenge at ‘the salt’ as

he called Bonneville.

In 1962, Burt shipped his Munro Special over to the other

side of the world, bought a station wagon for $90 which acted as Team Indian HQ

and, on a shoestring budget, took on the fastest ‘streamliner’ motorcycles in

the world on his 42-year-old home brewed Special - now bored out to 850cc. He

himself was 63 years old during that first attempt and was already a

grandfather. Yet he still astounded everyone present by establishing a new

world record at a speed of 178.971mph.

|

| The man and his machine, 1962 |

For most other people, it should have been the fulfillment

of a lifelong ambition but to Burt Munro, it was just all the more reason to go

faster still. Naturally, danger was never far away when travelling at such

speeds on hard-packed salt flats which feel like sandpaper to the touch - and

like a grinder when you skid along them at 170mph - but Munro didn’t let it

bother him. His account of one particular high speed tumble shows his

remarkable spirit. ‘At the Salt in 1967 we were going like a bomb’ he later

recalled. 'Then she got the wobbles just over half way through the run. To slow

her down I sat up. The wind tore my goggles off and the blast forced my eyeballs

back into my head - couldn't see a thing. We were so far off the black line

(the line marked in the flats which riders at Bonneville are supposed to

follow) that we missed a steel marker stake by inches. I put her down - a few

scratches all round but nothing much else.’

At the time Munro was travelling at close to 200 mph – and

he was 68 years old. On another occasion a con rod broke while he was pushing

195mph. Again, Burt was unfazed.

In a letter to fellow American V-twin enthusiast John

Andrews in England Burt wrote: ‘I had some of the worst out of control rides on

record. The worst was in 1962 when in an effort to stop wheel-spin at 160mph I

built a 60lb lead brick and bolted it in front of the rear wheel. By the time I

got to the three mile marker, the top of the shell was swerving five feet and

the wheel marks were five inches wide and snaking thirty inches every 200

yards. Well when you figure you can only die during your next skid, you try

anything, so I wound it all on for another one-and-a-half miles and when I

found out it would go on that way forever I rolled it back and got it stopped.

When the gang arrived and found me laughing and asked me the joke, I said I was

happy to still be alive.’

In 1967 Munro set the speed which officially made his bike

the world’s fastest Indian. To qualify to take part in the annual Speed Week at

Bonneville, riders must set a one-way timed run at a respectable speed. For

Burt Munro, that speed was an unthinkable 190.07mph. It was then, as it still

is now, the fastest speed ever officially recorded by an Indian motorcycle of

any kind.

What made Munro’s achievements even more remarkable was

that he was the only man who rode a ‘streamliner’ bike (fully-enclosed

motorcycles designed specifically for tackling speed records) in the

conventional manner - all other entrants had feet-first machines. And while

Burt had heavily modified the Indian’s frame, it was still the only one which

resembled a traditional motorcycle frame.

As Munro’s health deteriorated in the late 1960s his trips

to Bonneville lessened and in 1975 he finally lost his competition licence.

‘When dad realised he wasn’t going to be able to ride anymore he wanted me to

take over the Indian’ says John Munro. ‘I didn’t have the facilities or the

money so one of Dad’s motorcycling friends, Irving Hayes, who had a large

hardware store in Invercargill, bought the bike and put it on display in the

store. Irving’s grandson now runs the store and Burt’s bike is still on display

there along with one of the replicas from the movie.’

Up until 1968, Munro worked out that he had achieved an

average speed increase of 3.5mph every year for the last 50 years. By the end

of the bike’s development, Munro had coaxed around 100bhp out of a machine

which originally made just 18bhp.

On January 6th, 1978, Burt Munro finally

succumbed to the heart condition which had troubled him for many years. He was

78 years old. Yet he had never let his health problems stand in the way of

achieving his goals and fulfilling his ambition. As Burt once said of his

beloved Indian 'You live more in five minutes flat-out on a bike like this than

most people do in a lifetime.'

The Indian ended up in a hardware store in Burt's home town of Invercargill

Bronze memorial to the man and his obsession in New Zealand

Comments

Post a Comment