The Road Racers

The Making of a Classic

David Wallace's documentary film about the Armoy

Armada is an all-time biking classic. Shot in the summer of 1977, it followed a

then unknown Joey Dunlop, together with Mervyn Robinson and Frank Kennedy, as

they raced the Irish roads on a shoestring budget. Using pioneering techniques

such as on-board cameras, The Road Racers has become a cult classic

amongst bike racing fans. In a rare and exclusive interview, double BAFTA

award-winner director David Wallace takes us behind the scenes of the greatest

road racing documentary ever shot.

Words: Stuart Barker

Pictures courtesy of David Wallace

'Most people's image of bike

racing at that time was of Barry Sheene and all the glamour that surrounded him

with the Brut adverts on TV' David Wallace says. It was 1977. Sheene had won

his second 500cc world title and enjoyed a playboy lifestyle more reminiscent

of a rock star than a motorcycle racer. He had the Rolls Royces, the

helicopters, a Penthouse Pet hanging on his arm, and the world's press eating

out of his hand. Sheene had it all, and his success had made bike racing more

popular than it had ever been in Britain.

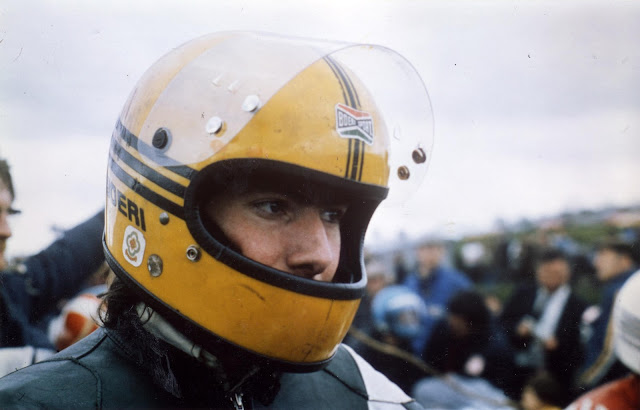

But there was another side to bike racing in the 1970s and David Wallace was determined to capture it on celluloid to complete the picture. As he says, 'Joey Dunlop was unlikely to be offered an after-shave advertising contract. I took some photographs in 1976 and his hair was so unkempt you could barely see his face when he was working on the bike.'

Even after becoming a five-times TT Formula One world

champion (the championship that was effectively replaced by World Superbikes),

Joey Dunlop didn't have too much time for appearances, but when Wallace worked

with him in 1976 and '77, he was a real diamond in the rough, living on the

dole in a council house and digging peat to keep his young family warm in

winter. Yet even then, the unkempt Irishman showed signs of the greatness that

was to come. 'There was no doubt about it that Joey was the one who was really

focused' Wallace says. 'I think his ability to concentrate singled him out. He

was completely into what he was doing and he was going to do it as well as he

possibly could. When I was taking photos at the Mid Antrim in 1976 I asked a

spectator where the bikes would land from the jump as I needed to get my camera

focused. He said “Well, they land all over the place – apart from Joey.

Wherever you see Joey land on lap one, you could put a coin down on the spot

and he'll hit it on every lap after that.” That summed Joey up. He was

disciplined. He was very fast and he was very fearless but he didn't fall off

that often. Merv and Frank did most of the falling off.'

'Merv and Frank' were Mervyn Robinson and Frank Kennedy,

the other two members of the Armoy Armada in 1977 (Joey's brother Jim would not

join the group until later). It was a serendipitous meeting with a relation of

Robinson's that led to the trio becoming the subjects of Wallace's first film.

'My neighbour was a man called Quentin Robinson' the director explains, 'and

when I mentioned to him that I wanted to make a film he said his nephew Mervyn

was a bike racer so he arranged an introduction. I didn't even know about the

Armoy Armada at the time. So I met Mervyn first. He was the most open, humorous

and impish of the three. He was a lovely warm character. Frank was a bit more

serious but fantastically friendly and helpful. Then Mervyn took me along to meet

Joey because they were related (brothers-in-law) and Joey was quiet, as you

would imagine. He didn't speak a great deal. He never said anything negative

but you got the impression that being in a film was probably the sort of

nuisance he could live without.'

It was clear that even in the early days, Dunlop was not comfortable in front of cameras – a trait that would continue throughout his career. 'To be honest, I think that Joey thought the others wanted the film to happen so he went along with it' says Wallace. 'He probably didn't realise just how much of an imposition it is having a film made about you. He managed to keep the nuisance value down by keeping a bit of distance but he was never unfriendly. If you said you wanted to come and film in his garage the night before a race that wasn't a problem. You could film what you liked and stay as long as you liked but, for example, if you were shooting and you missed something happening and asked if you could shoot it again he'd say “Look, it'll make all our lives easier if we just get it right first time, every time.” With the other riders you could do as many re-takes as you liked but with Joey you just had to be that bit more efficient. He always got his part right first time so it was almost as if he was saying “Look, I can do it, why can't you?” Of course he would never have said that, but it was difficult to ever really know what Joey was thinking.'

The film was made on the tightest of budgets using borrowed

equipment and a great deal of goodwill. Wallace's background was in making

short educational films for the BBC's Schools Department and he really wanted

to make a feature-length documentary of his own, though bike racing wasn't the

first idea he pitched when he approached the Northern Ireland Arts Council for

funding. Thinking they would want something 'arty' he offered up ideas on the

local harvest and on Irish poets, neither of which stirred any interest in

Brian Ferran, the man holding the purse strings. 'I only had the motorbike idea

left' Wallace says 'so I pitched that, promising it would be very artistic

because I thought that was what he wanted to hear. He looked up and explained

that his family used to have a summer house in Portrush and as a boy he'd run

out to the front gate to watch these motorbikes rushing past at 100mph. It had

clearly left a big impression on him and he wanted to know how it all happened

– how bikes could be raced on public roads. And that was exactly what I

really wanted to make a film about.'

Wallace left with a £4,000 grant though it wasn't nearly enough. After securing various other sponsors and ploughing around £4,000 of his own money into the project, he had a total budget of £9,000. It was just about enough to shoot the film and he would worry about post-production later. Wallace took three weeks leave to shoot the film, primarily with one camera, though others were borrowed from time to time as favours were called in. 'I paid the cameraman, the sound recordist, and the production assistant £50 a week out of my own pocket and I provided accommodation for them by hiring a little cottage' Wallace says. 'The riders didn't get paid anything. The BBC didn't pay people for documentaries back then and, up to a point, they still don't. At that point, I was nearly as poor as the guys were.'

Yet necessity is the mother of invention and Wallace didn't

allow a shortage of funds to cramp his innovative style. The Road Racers

featured stunning on-board camera work years before it became commonplace.

Wallace explains 'I bought a gun camera that had been used on fighter planes

(gun cams were synched to the aircraft's machine guns to record any hits) and

our sound engineer made all the bracketing to fit it to the bikes. We got the

guys to do one meeting each with the camera. Joey was up first doing the North

West. The camera itself was quite small but the battery was quite bulky so it

had to be strapped somewhere else, like under the seat. In Joey's case we had a

problem, and Joey didn't like problems. He didn't like complications – he just

wanted things to work. When he came for his bike we had the camera fitted but

the battery still wasn't attached and Joey didn't want to wait. I said we were

going to have to forget it but Joey asked what the problem was. When I told him

we hadn't mounted the battery he said “Is that all? That bit of metal?” When I

said yes he jumped on the bike and put the battery between his legs and rode

off. The only thing holding that battery on during a lap of the North West 200

at racing speeds was Joey's knees.'

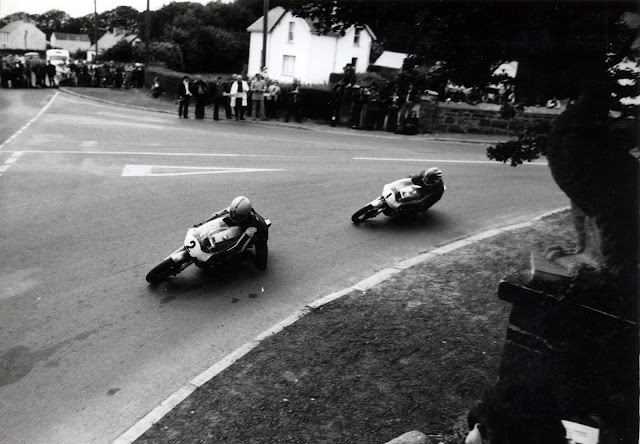

The opening shot of the film showsMervyn Robinson

illegally testing his race bike on small country lanes, scattering sheep in all

directions. The shot perfectly summed up the maverick spirit of Irish road

racing in the Seventies. Wallace explains how the idea came about. 'I had asked

Joey what it was like testing a race bike late at night on country roads and

was he worried about the police? He said “I'm far more worried about the sheep”

so that's where the idea for the opening shot came from. We set the shot up so

it was just a timing thing. We had to be sure the farmers could get the sheep

off the road before the bike arrived at speed. I think the health and safety

brigade would have had something to say about that now!'

Had they existed back then, the health and safety brigade

would have been in an even bigger flap by the impromptu methods used to get the

aerial shots seen in the film. 'They were filmed by an NBC war cameraman who

had done Vietnam and the Israeli wars' Wallace says. 'We had both been in the

university air squadron and had been taught to fly by the RAF. He said he could

get an aerial shot so I gave him the camera and he and a friend who had a plane

took off to get some shots of the bikes racing along the coast road at the

North West. Unfortunately, we hadn't thought it through properly as the door

was on the pilot's side so the cameraman couldn't hang out to get the shot.

They couldn't change seats in the air so they landed, changed seats, and my

friend, who hadn't flown for about five years and probably didn't have a

pilot's licence at that point, took off and flew the plane back up to the

circuit. He then hung out of the pilot's door to get the shots while the other

guy reached over and held the controls! The tricky bit came after when my mate,

who also hadn't landed a plane in five years, had to land it all by

himself, but somehow he managed without mishap.'

A native Ulsterman himself, Wallace had no problem

understanding Dunlop, Robinson and Kennedy's accents but it wasn't quite so

simple for others. 'When I showed the film to people in the UK they said they

couldn't understand a word they said – they had no idea what they were talking

about. So I explained the problem to the riders and they all agreed to be

interviewed again and to speak in what they called their 'Sunday-go-to-meeting'

voices. It's still their voices but it would have been more fun for me if we

could have used their natural accents.'

Although all the footage was shot at the Cookstown 100, the

Carrowdore and the North West 200 in 1977, the film didn't get aired until

1980, again due to budget and time constraints. 'I had to persuade editors to

give their time for nothing and they had to find spare time to do the editing'

Wallace says. 'One of my in-laws provided an editing machine – you couldn't

just do it on a lap top back then, you needed an editing machine and an editing

room.'

Four years after the project was begun, The Road Racers was finally aired on BBC Northern Ireland in 1980 before being transmitted to the rest of Britain on BBC2 and it continues to sell on DVD to this day, even though the original film no longer exists. 'All the film was destroyed' Wallace says. 'It was standard practice back then. It wasn't exactly a prized film.'

It's a prized film now, providing, as it does, not only a

perfect snapshot of Irish road racing in its 1970s hey day, but also unique

early footage of Joey Dunlop before he became a superstar. It also became a

tribute to Frank Kennedy and Mervyn Robinson who both died in separate

incidents at the North West 200 (in 1979 and 1980 respectively) while the film

was still going through the long drawn out post-production process. 'After

Frank was killed we talked about what we were going to do with the film' Wallace

says 'but I don't think we ever considered not finishing it. I mean, it

would have been easy to have had an instantaneous reaction and felt that it was

no longer in good taste but of course it was in good taste. I've met Mervyn's

son Paul Robinson and lots of other people since then and most of them consider

that it was a good thing to have that recording of Frank and Mervyn.'

Joey himself could never bring himself to watch the film;

it was too painful a reminder of the loss of his two great friends. Tragically,

he too would lose his life in a racing crash, many years later, in Estonia in

2000. By that point, David Wallace was a BAFTA award winning film-maker who

travelled all over the globe shooting documentaries. Such was Dunlop's fame by

then, Wallace could not escape the sad news of his death no matter where he

was. 'I was doing a series called Conquistadors about the Spanish conquest of

South America and I think I was in the Amazon at the time. My wife had heard

the news about Joey on the radio and the next time I spoke to her on the phone

she told me about it. It was a huge shock. I didn't make it back in time for

the funeral but I saw pictures from it in the strangest places because it was

such a momentous event.'

So 20 years after his film was first aired, it's three

subjects had all been killed in racing accidents. Understandably, David Wallace

now has mixed feelings about road racing. 'I totally admire road racers and

part of me thinks it's wonderful, but there's another side of me that says it's

illogical and that surely someone's going to put a stop to it sooner or later.

I don't have a fixed opinion – I still can't make my mind up. If I ruled the

world would I ban road racing? Probably not, I'd probably just leave it up to

others to decide. But I'm not as gung-ho about it as I was when I was younger.

I'm in two minds about road racing now: one says it's completely daft and the

other says it's absolutely wonderful.'

One thing Wallace isn't in any doubt about is his lasting admiration for Joey Dunlop. Another of his successes as a film-maker was the four-part series 'In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great.' Wallace draws an interesting comparison between the Macedonian king and the quiet hero from Ballymoney. 'There's a wonderful Greek song about Alexander at the end of the film that says “Alexander, you conquered the whole world but you lost your soul.” That's one thing you could never say about Joey – he conquered the world but he absolutely kept his soul.'

What's in a Name?

'The Road Racers is a

very ordinary title. My original idea was to call the film 'The Race for

Seconds' and there was a subtitle I considered 'For Champagne Read Guinness'

but that would never have worked because the guys never drank Guinness, it was

always vodka and coke! The other title came from the closing line in the film

after Mervyn wins the race. He says 'Boys, there's piles of room to go harder.'

I really liked that but it was too obscure – it would just have confused

everybody. The title in the end came from an English executive producer who

actually had nothing to do with the film. He said I needed a title that told

the audience exactly what they were going to see. He had a 'Don't be clever –

this is television' type of attitude. You can do intriguing titles in cinema

but TV doesn't lend itself to intriguing titles. People need to know what it's

going to be about so this guy asked me and I said “It's about people who race

on real roads” so he said “Well why don't you call it The Road Racers?” Funnily

enough it kind of worked.'

The Road Racers II: A

Missed Opportunity

In 2009, the first new road race to be staged in Northern Ireland for 50 years was held in Armoy as a tribute to the Armoy Armada. David Wallace almost made a film about the event that his original documentary helped to create but in the end it never happened. Here's why:

'I toyed with the idea of

shooting a film about the Armoy road races and went as far as speaking to BBC

Northern Ireland about putting the old team back together again but nobody knew

if the race was actually going to happen until quite near the time and the BBC

said they couldn't really see a story there anyway. That seemed to me to be a

pretty amazing thing to say given that it was the first new road race in

Northern Ireland for 50 years and it's one of the most popular sports in

Ireland, so that seemed a bit crazy. And with the legendary status of the

people involved in road racing from Armoy you'd have thought they'd have gone

for it but in the end I didn't push it very hard because I would have needed

the time to get back into the community again and in the end BBC Northern

Ireland couldn't make its mind up quick enough.'

Comments

Post a Comment